Who Stole My Cookies? XSS Vulnerability in Microsoft Azure Functions

Published 01/11/2023

Originally published by Pentera.

Written by Uriel Gabay, Pentera.

Purpose

Learn how Pentera’s research team discovered a web XSS vulnerability in Azure Functions and determined its exploitability. The vulnerability was reported and fixed by Microsoft.

Executive summary

Cloud-based services are a growing asset for enterprises to optimize scale and reduce deployment efforts. In our research, we found a web XSS vulnerability on Microsoft Azure Functions due to an improper implementation of access control. This paper shares a behind-the-scenes window into our process of discovering the vulnerability and developing a proof of concept that demonstrated its exploitability. Following our report, the vulnerability was patched by Microsoft in Q1 of 2022.

Does it apply to my organization?

Not any more. This cloud vulnerability was fixed at the source on Azure servers, and is no longer exploitable.

Who should read this?

Cyber experts and aficionados interested in professional growth and learning about unconventional web attacks. The methods presented in this paper are likely to prove an interesting starting point for further research.

Attack surface domain

Cloud, Azure, Web, Server and Client-side attacks.

Relevant MITRE ATT&CK TTPs

Exploit Public-Facing Application T1190

Browser Security Concepts

The browser is responsible for client-side security measures aimed at limiting the web attack surface as much as possible. One of these is sandboxing, a mechanism aimed at isolating each accessed origins on the client-side, so that accessing a malicious origin will have no effect on other concurrently connected origins or the data they store, such as cookies, databases or storage.

Another basic client-side security measure is SOP (Same Origin Policy). SOP is a basic browserenforced standard that prevents origins from sending information directly from one domain to another when the HTTP request is unique. Essentially, it prevents sharing of data across origins. A unique HTTP request requires the right CORS permission.

Here are some examples of unique HTTP requests:

- Unique content-type - application/JSON, application/xml

- Unique HTTP method - PUT, DELETE, PATCH

- Etc.

If the HTTP request is unique, the browser will send preflight (OPTIONS) requests to inspect the CORS policy and ascertain if the request can be permitted.

CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing)

SOP aims to prevent direct unique HTTP requests to other domains, and as part of the preflight

flow an OPTIONS request is sent in advance.

The CORS policy is passed via an HTTP header, which indicates to the browser what the policy

is for accepting “unique” HTTP requests.

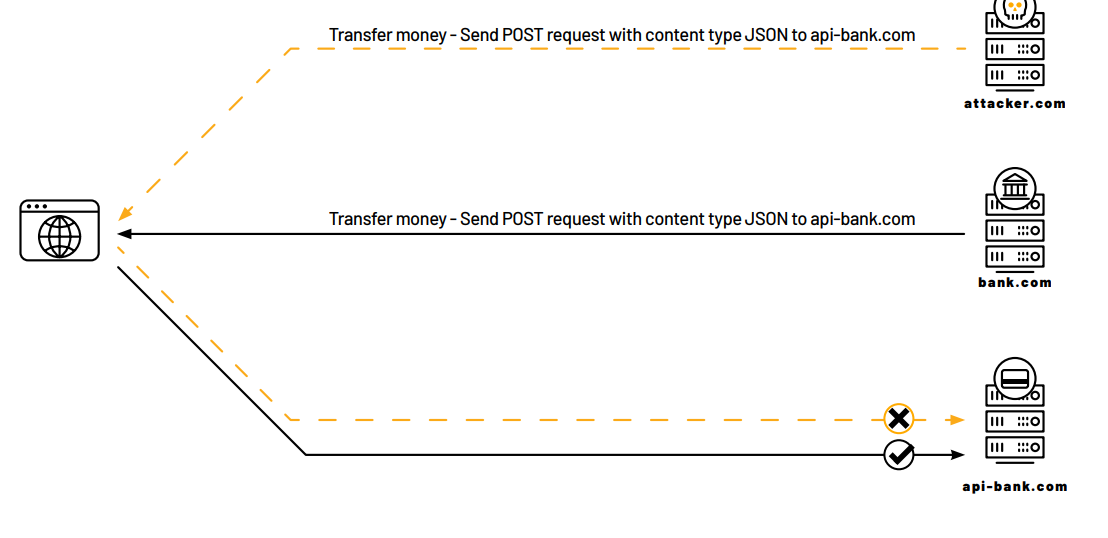

Let’s consider an example. Imagine a company “Bank” that has 2 websites:

- “bank.com” which contains all static files for the website (HTML, CSS, JS, PNG, and more).

- “api-bank.com” which implements all the dynamic logic of the website and is responsible for all banking actions performed from the website. This website accepts JSON content-type.

From the browser’s perspective, the client accesses “bank.com” and then “bank.com” tries to access “api-bank.com” to get dynamic information for the specific client.

If CORS policy on api-bank.com allows bank.com to communicate with it (black lines), then the requests from bank.com would be released by the browser and sent to api-bank.com. All other origins would be blocked.

The following flow will be forced:

XSS (Cross-Site Scripting)

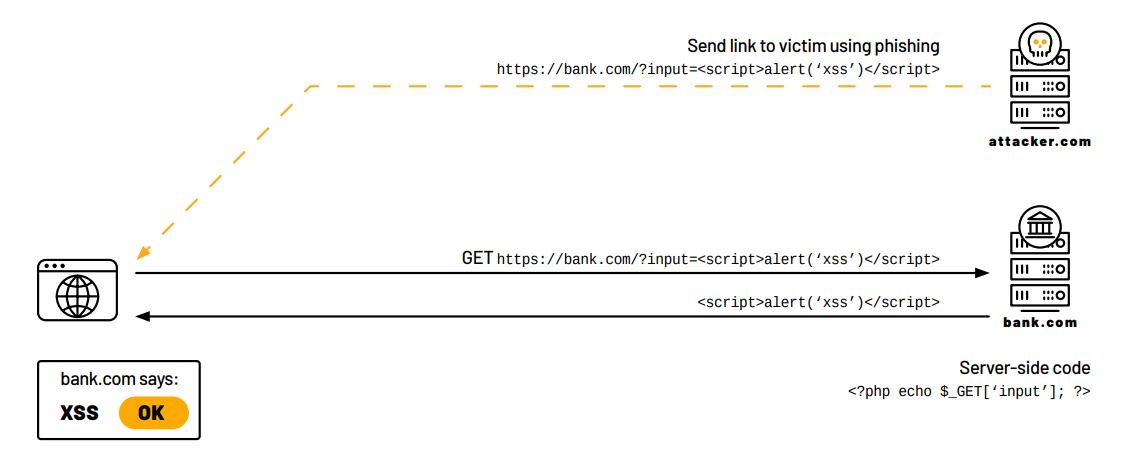

XSS is a category of code injection aimed at injecting malicious scripts into otherwise trusted origins.

Such vulnerabilities occur when user input is not properly sanitized and can be used as a vector for client-side scripts, which are then rendered by the browser. They give the attacker the ability to run JavaScript code within the context of a legitimate website.

There are 3 main types of XSS:

- Reflected – The malicious JS code is triggered by the specific client by leveraging an input which is reflected to the client

- Persistent – The malicious JS code is permanently injected into the website data (DB, static files, logs, etc.) and is presented to users by the server

- DOM – The malicious JS code is executed in the context of a legitimate client-side code section belonging to the website

Our investigation focused on reflected XSS, where the malicious code gets sent back by the server to the client following a malicious HTTP request which contains it.

Below is an example of the flow we are interested in:

Azure Functions

Azure Functions provides an auto-scaling cloud service available on-demand for developing websites that can run code sections without having to worry about resources, updates, and operational maintenance.

Our findings concern one of the domains used by Azure to serve their Functions platform services: functions.azure.com

Discovery of the Vulnerability

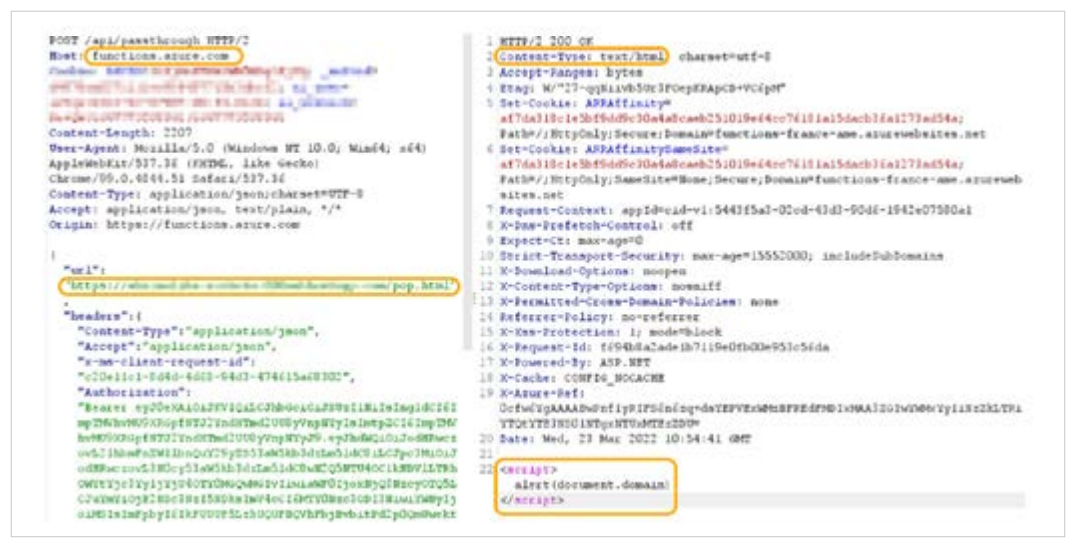

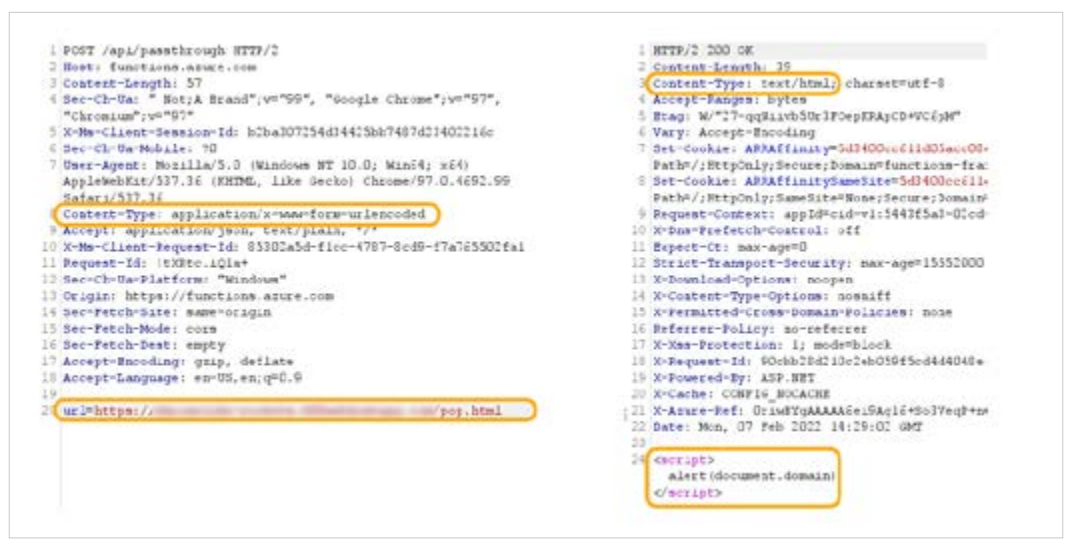

After setting-up a function app resource, we intercepted the traffic originating from the browser to the Azure portal, and we noticed the following request had been sent to “functions.azure.com”:

A parameter called “url” piqued our interest. The request indicated that “functions.azure.com” was sending a request to the website in the “url” along with the headers and body configured in the parameters.

Since the content-type of the response is “text/html”, this means that the browser will try to parse the response as HTML, a well known launchpad for XSS attacks.

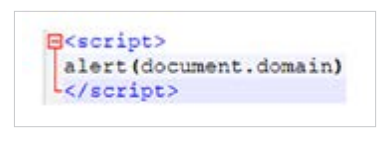

With this information at hand, we created a simple HTML web page containing an embedded script:

The screenshot below shows what happened next: After we passed the address of our malicious

HTML to the url parameter, we noticed that the script was contained in the response, unsanitized

and unencoded, and under the functions.azure.com context.

At this point, all we needed was to create a simple HTML form to send this request automatically and exploit the XSS in “functions.azure.com”.

This may seem trivial and straight-forward, however, the content type of the request is application/json. Owing to the SOP mechanism, we cannot send “unique” HTTP requests directly to a website that is not part of the same domain.

Additionally, we needed to send the request over an HTML form for the redirection to be followed automatically. Again, sending application/json content type cannot be done via HTML forms.

To execute the attack, we depended on the server supporting x-www-form-urlencoded content type for the following 2 purposes:

- Bypassing SOP (text/html) with non-unique HTTP requests to avoid preflight.

- Ability to execute our requests using an HTML form, which does not support application/json

We needed to get rid of application/json content type. So, in our next attempt, we tampered with the format of the body of the request to fit x-www-form-urlencoded content, hoping that the remote server (“functions.azure.com”) would accept it; and against all odds, it did!

we had achieved full-fledged XSS on “functions.azure.com”.

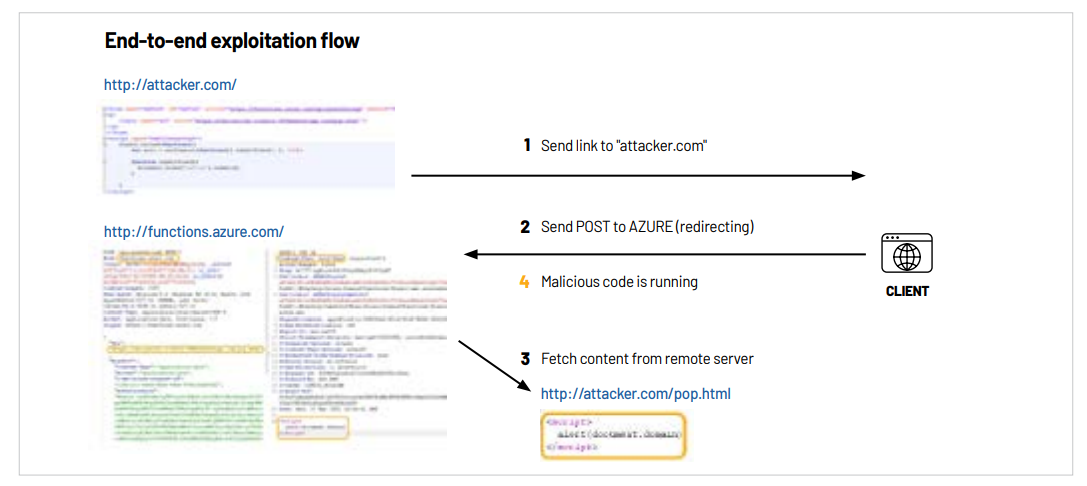

Up to this point, we have seen how we, as researchers, can tackle the discovery of this

vulnerability. However, the attacker point of view is somewhat different, as presented in the

following diagram:

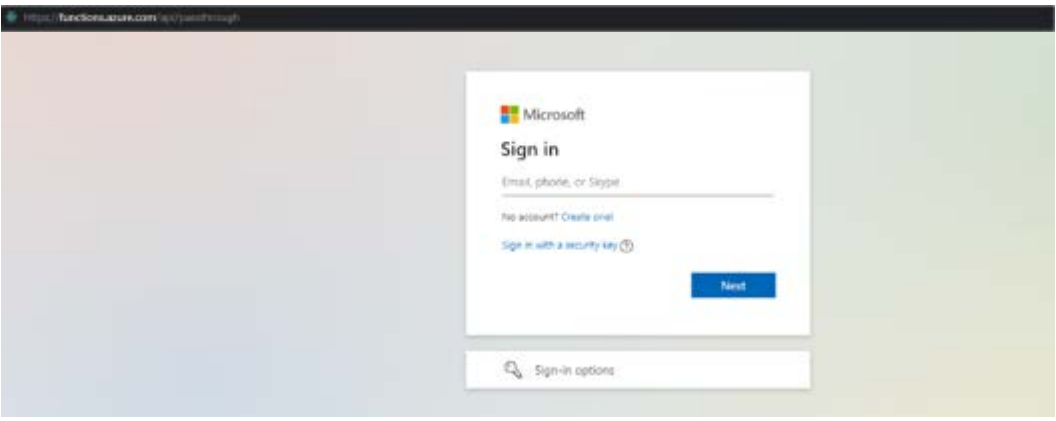

Of course, the malicious HTML can contain any content, for example, to leverage phishing techniques. The page will be displayed in the context of functions.azure.com. We could even produce a very legitimate looking login form for phishing purposes, as in the following screenshot. As a phishing site, this would likely prove highly effective and quite damaging.

Conclusion

After demonstrating how we uncovered an XSS vulnerability in Microsoft Azure Functions

including key security concepts and the attack chain, you should now be able to leverage attacks

and protect assets in a better way.

About the Author

Uriel Gabay is a Senior Security Researcher and exploit developer at Pentera. Prior to joining Pentera, Uriel served in a classified unit in the IDF, specializing in application security and Red Teaming. For any questions, feel free to reach out at [email protected]

Unlock Cloud Security Insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest expert trends and updates

Related Articles:

Agentic AI Pen Testing: Speed at Scale, Certainty with Humans

Published: 01/26/2026

My Top 10 Predictions for Agentic AI in 2026

Published: 01/16/2026

.png)

.jpeg)